New study reveals negative sustainability implications of “slower growing” raising methods; NCC supports more research on chicken welfare

WASHINGTON, D.C. – NCC urges consumers, the foodservice and retail industries, and non-governmental organizations to invest in studying the impact in the U.S. of the growing market for “slower growing” broiler chickens. A study released today by the National Chicken Council (NCC) details the environmental, economic and sustainability implications of raising slower growing chickens, revealing a sharp increase in chicken prices and the use of environmental resources – including water, air, fuel and land. NCC also calls for more research on the health impact of chickens’ growth rates, to ensure that the future of bird health and welfare is grounded in scientific, data-backed research.

“The National Chicken Council and its members remain committed to chicken welfare, continuous improvement and respecting consumer choice – including the growing market for a slower growing bird,” said Ashley Peterson, Ph.D., NCC senior vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs. “However, these improvements must be dictated by science and data – not activists’ emotional rhetoric – which is why we support further research on the topic of chicken welfare and growth rates.”

Environmental Implications

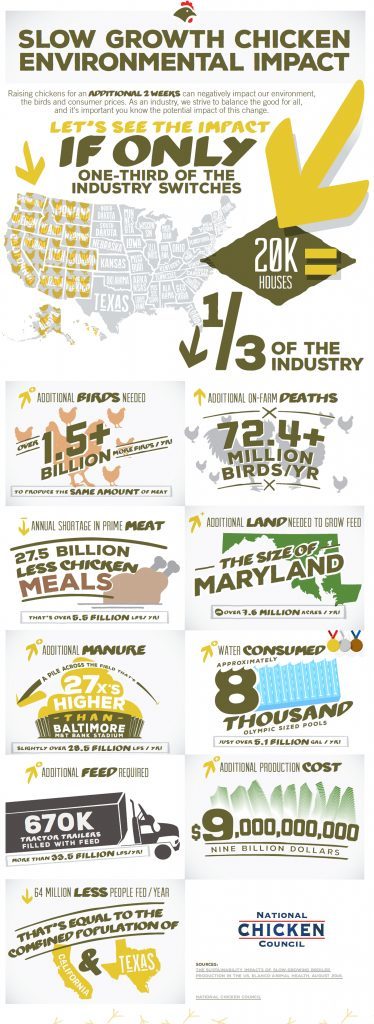

In assessing a transition to a slower growing breed, the environmental impact is an important component often left out of the equation. If only one-third of broiler chicken producers switched to a slower growing breed, nearly 1.5 billion more birds would be needed annually to produce the same amount of meat currently produced – requiring a tremendous increase in water, land and fuel consumption:

Additional feed needed: Enough to fill 670,000 additional tractor trailers on the road per year, using millions more gallons of fuel annually.

Additional feed needed: Enough to fill 670,000 additional tractor trailers on the road per year, using millions more gallons of fuel annually.- Additional land needed: The additional land needed to grow the feed (corn and soybeans) would be 7.6 million acres/year, or roughly the size of the entire state of Maryland.

- Additional manure output: Slower growing chickens will also stay on the farm longer, producing 28.5 billion additional pounds of manure annually. That’s enough litter to create a pile on a football field that is 27 times higher than a typical NFL stadium.

- Additional water needed: 1 billion additional gallons of water per year for the chickens to drink (excluding additional irrigation water that would be required to grow the additional feed).

Economic Implications

If the industry did not produce the additional 1.5 billion birds to meet current demand, the supply of chicken would significantly reduce to 27.5 billion less chicken meals per year.

The additional cost of even 1/3 of the industry switching to slower growing birds would be $9 billion, which could have a notable financial impact on foodservice companies, retailers, restaurants and ultimately – consumers. This will put a considerable percentage of the population at risk and increase food instability for those who can least afford to have changes in food prices.

A reduction in the U.S. chicken supply would also result in a decreased supply to export internationally where U.S. chicken is an important protein for families in Mexico, Cuba, Africa and 100 other countries.

NCC’s Commitment to Chicken Welfare and Consumer Choice

“Slower growing,” as defined by the Global Animal Partnership, is equal to or less than 50 grams of weight gained per chicken per day averaged over the growth cycle, compared to current industry average for all birds of approximately 61 grams per day. This means that in order to reach the same market weight, the birds would need to stay on the farm significantly longer.

For decades, the chicken industry has evolved its products to meet ever-changing consumer preferences. Adapting and offering consumers more choices of what they want to eat has been the main catalyst of success for chicken producers.

“We are the first ones to know that success should not come at the expense of the health and wellbeing of the birds,” said Peterson. “Without healthy chickens, our members would not be in business.”

All current measurable data – livability, disease, condemnation, digestive and leg health – reflect that the national broiler flock is as healthy as it has ever been.

“We don’t know if raising chickens slower than they are today would advance our progress on health and welfare – which is why NCC has expressed its support to the U.S. Poultry and Egg Association for research funding in this area,” said Peterson. “What we do know is there are tradeoffs and that it is important to take into consideration chicken welfare, sustainability, and providing safe, affordable food for consumers. There may not be any measurable welfare benefits to the birds, despite these negative consequences. Research will help us identify if there are additional, unforeseen consequences of raising birds for longer.”

NCC in 2017 will also be updating its Broiler Welfare Guidelines, last updated in 2014, and having the guidelines certified by an independent third party. The guidelines will be updated with assistance from an academic advisory panel consisting of poultry welfare experts and veterinarians from across the United States.

“NCC will continue to be in the business of providing and respecting consumer choice in the marketplace,” Peterson concluded. “Whether it is traditionally raised chicken, slower growing breeds, raised without antibiotics or organic, consumers have the ability to choose products that take into account many factors, including taste preference, personal values and affordability.”

For additional information and resources about how chickens are raised, visit www.chickencheck.in.

Study Methodology

The study was conducted August-September, 2016 by Elanco Animal Health, in consultation with Express Markets, Inc., using a simulation model that estimates the impact of slow-growing broilers on feed, land, water utilization, waste/manure generated, and production cost. The model used average values of conventional vs. slow-grow broiler for mortality, grow-out days, feed conversion, days downtime, and placement density. A full copy of the study is available here.